Alysa Nahmias directed and produced the 2023 Emmy-winning feature documentary ART & KRIMES BY KRIMES, which won Best Arts and Culture Documentary (distributed by Paramount+/MTV Films), and produced the 2023 Emmy-winning Amazon Studios release WILDCAT, which won Best Nature Documentary. Her production company AJNA has produced numerous other acclaimed projects for over a decade. As a Co-Founder of FWD-Doc, Alysa is also an advocate for disabled people in the entertainment industry.

Alysa sat down with Dear Producer to discuss her journey as both a director and producer in the documentary space, her sense of responsibility to the subjects in the films she makes, and how she measures success beyond awards and accolades. She also shares how she’s carved a full-time career as a filmmaker and what she wants to impart to new filmmakers looking to enter into this profession.

There are many different entry points for a producer to join a film, which is especially true in documentaries where filmmakers are often filming a subject long before anyone else is involved in the film. On WILDCAT, when did you come on to the project?

It’d be cool if I told you I was just out in the middle of the jungle and stumbled upon the story, but that was not the case. However, it was the case for one of the directors, Trevor Frost. He had been a photographer for National Geographic, and Melissa Lesh, Trevor’s co-director, had made some beautiful short films in the conservation space. Trevor stumbled on the story while he was in Peru photographing anacondas and met Harry Turner and Samantha Zwicker, the protagonists of the film, at the wildlife rescue center Hoja Nueva where the film takes place.

Trevor and Melissa began filming for many months before involving anyone. Raising the ocelot (a medium-sized spotted wild cat) was an 18-month process so they knew that the project would take at least that long to shoot. They shot it on a shoestring budget, and actively involving Harry and Samantha in the cinematography and field producing.

We were introduced by a mutual friend when they were more than halfway through production. They had an investor who was interested in the project and this filmmaker friend told them they should talk to a producer who was familiar with investor agreements before they sign anything. That was my entry point. I helped them through that contract and also asked them about what chain of title existed with the film’s participants and with each other. We also talked a lot about their creative vision for the storytelling and how to navigate the sensitivities of collaboration under such intense circumstances.

I immediately fell in love with the project and hit it off with Trevor and Melissa. The story they were telling was incredibly powerful, and their collaboration with Harry and Sam was uniquely immersive and personal. They also demonstrated a capacity to strategize about how best to share their story with a big global audience. One of the things I look for from directors is receptivity. When I suggest something, are they going to follow through or at least have a meaningful conversation about the idea? Also, asking great questions and having high aspirations is important to me. I saw all those wonderful things in them and said I wanted to stay on if they would have me as a producer on the project. It was the one project I could take on at the time as more of a labor of love. We all had a big vision for it and feel grateful for how it worked out.

We collaborated intensively on the business side of making Wildcat, and they also welcomed my creative and strategic voice on the team throughout. A lot of times, what directors think they need is money – and they do need it – which often sparks them to reach out to producers under the assumption that we can help make money magically appear, but there is so much more we have to offer.

I often get directors who reach out to me and say, ‘I just need you to raise money for me, you don’t have to do anything else.’ What they don’t realize is that if I’m going to bring financing to your film, I am responsible to that financier and their money. I need to be involved so that I can ensure there is fiscal responsibility when making the film.

Totally. I think it gave confidence to that first investor, and then the others we brought on, that Josh Altman (my producing partner on the film) and I had long positive track records. We could think strategically in light of past lessons learned on other films, and we asked tough questions about priorities such as how much control we were willing to give up when raising money and what financiers were the right fit for the team. We found both of our early independent executive producers who took a chance on the project, as well as 30West, were a great match for the team.

It looked as though Harry shot a majority of the footage, is that correct?

Melissa and Trevor each clocked a few hundred days in the jungle, both filming and teaching Harry and Samantha how to shoot. One of the constraints of production was that to rehabilitate and re-wild the cat, it can’t connect with any humans besides Harry. Even Samantha had to keep her distance. Melissa and Trevor could film on the platform (their dwelling in the jungle), but they couldn’t film on the walks with the cat. That was all filmed by Harry, who is credited as a cinematographer on the film.

Were there any particular safety issues or ways you set Trevor and Melissa up that were unique to this environment?

Melissa, Trevor, Harry, and Sam had become very close before I became involved in the project. The four of them slept on the same platform and ate their meals together during the months when they were filming. This is unusual, for the directors to be living with the subjects of their film, but there wasn’t anywhere else to stay. It’s really a remote location. It does create an intimacy that audiences feel on screen.

My contribution to the production was to support the directors and film participants on their journey together. I encouraged the directors to continue to get the mental health support that they might need because, as you know if you’ve watched the film, there were some really challenging things going on around trauma and relationships. Letting go and healing are big themes of the film. I was doing my best to be supportive of them remotely and also, when they were back in the States, to encourage them to do a lot of self-care and to stay optimistic and strategically-minded about the future of the project.

It required being tuned in emotionally as well as professionally. Trevor has been public about struggling with anxiety and depression. I drew upon not only personal experience with loved ones, but also the work I do as a founding member of FWD-Doc and supporting disabled filmmakers. Trevor ended up joining FWD-Doc and befriending one of my co-founders, Jim Lebrecht, identifying as a disabled filmmaker, and finding community and support there.

Members of the WILDCAT film team at the 2023 Telluride Film Festival for their world premiere.

Left to right: Mallory Bracken (co-producer), Samantha Zwicker (field producer, film participant),

Trevor Beck Frost (director/producer/DP), Melissa Lesh (director/producer/DP/editor),

Alysa Nahmias (producer), Harry Turner (cinematographer, film participant),

Joshua Altman (producer, editor)

I recently watched STOLEN YOUTH: INSIDE THE CULT AT SARAH LAWRENCE and there were some moments towards the end where, as a viewer, it was really hard to watch because I was so worried for the subjects’ mental health. How does a director keep a distance and perspective when it’s clear the people you are filming are struggling?

It is particular to each person involved with the project. One thing that we can all do is have really open conversations about it and take the most wise and compassionate action that we can. Melissa and Trevor did. You don’t see all of it in the film, obviously, but it was happening behind the scenes. For example, when Samantha decides to make a call to get help, they were really supportive of that, and Trevor (who filmed that scene) encouraged her to make the call. When Harry needed to leave, they were really involved with that more than you see on camera. They were supportive as people first, as friends first. They would re-affirm consent repeatedly that Harry and Samantha did want to film difficult moments. Also, Trevor and Melissa put down the camera a lot and made sure there weren’t any instruments of self-harm available at times. You have to protect life first. I think, on some level, Harry and Samantha knew that sharing their story could be useful to others, and it has been.

I’ll say one thing, too, that’s interesting about the mental health crisis. It is really hard to watch people suffer. I do think – and this is my personal opinion – there are certain misconceptions out there around mental health that will have us believe that somehow, with mental health conditions, someone else can save the person, that an un-trained yet compassionate individual might somehow heal or “fix” them.

My father and stepmother are psychiatrists, and I have family members with mental health conditions, so I grew up with a lot of exposure to talking about mental health in my family. I had a relationship and understanding of mental health conditions that stopped me from thinking that we as filmmakers could or should change Harry. I think we could be good friends to him and responsible filmmakers working with him and very supportive, but we couldn’t change him any more than we could cure someone with cancer.

What’s more, my involvement with FWD-Doc has let me to understand disability in terms of the “social model” developed by disability rights activists in the 1970s and 80s, which views the origins of disability as the mental attitudes and physical structures of society, rather than a medical condition faced by an individual, then PTSD and depression are not abnormalities to be “fixed” but part of our shared humanity. The issue is society’s failure to provide services and accommodations. For some people, opportunities to connect with animals might be a form of access that transforms a person’s heightened sensitivity from a perceived negative into a strength, as it did for Harry.

I can’t imagine how difficult it was, the two of them isolated in the jungle doing this hard thing together. Watching how they both handled the situation was heartbreaking, but really affirming in that they both knew what was best for themselves.

We wanted to convey that, and how it paralleled their thinking that the cat was the one that they were letting go of, but really, for the audience, it’s about whether or not Harry and Sam will make it. Our whole team shared a powerful vision and worked incredibly well together to shape the emotion of the story.

Switching gears… In addition to winning an Emmy for WILDCAT, you also won an Emmy for ART & KRIMES BY KRIMES, which you directed. At what point did you decide you wanted to direct as well? How do you choose which projects to direct vs produce?

I actually didn’t switch from producing to directing. I started off making a film that I was directing and producing, so it’s been that I’ve always played both roles. That film was called UNFINISHED SPACES, about the Cuban National Art Schools that came out in 2011. It was the first film that I co-directed and produced with Ben Murray, who has become a longtime collaborator (he produced ART & KRIMES BY KRIMES and was Post Producer on WILDCAT). I had been studying architecture and art, and while on a trip to Havana and I met one of the architects who designed the art schools there in the ’60s. While visiting the buildings, I told him that someone should make a film about this story because the spaces were extraordinarily cinematic. He dared me to make it myself. Ten years later it was released.

I had to learn it all by doing. I didn’t go to film school like Ben did, so I learned from him and from my mistakes along the way. I had to figure out how to raise the money, build the team, tell the story, and shoot it all. I even did sound for that movie and Ben was the cinematographer. The film came out six weeks after my daughter was born, so I had my first human baby and my first film “baby” that arrived at the same time. It was both wild and wonderful. My daughter’s first trips were for the premiere at the LA Film Festival and the premiere at the Havana Film Festival and my husband Rob came with us so it was a family affair.

Producing was something that I was drawn to, but also, frankly, something that people asked me to do. It wasn’t like people were going after a female director in 2011 and asking, “What’s your next project? We want to finance it.” However, they did say, “Will you produce my next project?” I’ll be honest and say I don’t know how much of that had to do with gender, but I would venture that it wasn’t nothing. I co-directed UNFINISHED SPACES with a man and there were a lot of assumptions from the outside about who did what.

In choosing which films I direct or produce, there are several factors I keep in mind. If I solely originate a project, so far it’s been one that I want to direct. The projects I’m producing are either co-originated with a director or they are directed by artists like Melissa and Trevor who seek me out, or directors like Mariam Ghani or Amber Sealey who I’ve known that I wanted to collaborate with as soon as I saw their past work. It’s always directors whose visions I greatly believe in and want to get behind. That’s been the way I’ve operated. I’m also now actively looking to collaborate with other producers who I respect. For example, I’m producing alongside Keith Wilson (who I also worked with on Reid Davenport’s I DIDN’T SEE YOU THERE) on director Todd Chandler’s next feature documentary, and I’m producing a new project with Su Kim and Rodrigo Reyes. I’m also directing a feature documentary which I’m producing with Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw (THE TRUFFLE HUNTERS) and Jennifer Sims that I’m quite excited about.

How did you find the story for ART & KRIMES?

It’s my third feature doc as a director, but I started making it in 2014, before I started THE NEW BAUHAUS, which came out first. I read a blog post about an artist named Jesse Krimes who had created this large-scale work in prison and saw a picture of him with the work. I couldn’t get it out of my mind and reached out to him wanting to connect as artists. He asked to see my films, so I sent links and asked him what he was up to and if he had support. He was still in a halfway house at the time. We got to talking about what it would mean to make a film that told his story.

I thought it could’ve been a short film, but when I went to visit him, he introduced me to the other artists in the film, and we realized it could be much bigger, making a statement not only about the impact of mass incarceration, but the inherent value of human life, friendship, and second chances. My first call was to Ben Murray who had co-directed UNFINISHED SPACES with me, and he ended up producing and doing cinematography for the first shoot with me. This was also the first time I got to work with a producer I didn’t already know, but she came on board because she believed in my project. That was Amanda Spain who is a brilliant nonfiction producer. I met Amanda when Kristin Feeley (Director of Labs, Artist Support and Creative Producing, Documentary Film Program at the Sundance Institute) set us up on a date as producers to meet. We just started talking about projects and I said, “I also am doing this thing that I’m directing…” and she said, “Oh my God, I want to do that with you if you need someone.” She stayed with it for the long haul, helping me raise the financing, shape the film’s edit and animation, and strategize for distribution and impact. It was a small but mighty team, and all of our department heads were women, including trans and BIPOC women, which made for a feminist approach to telling a story that we all lovingly recognize is a bromance.

Alysa Nahmias on stage accepting the Emmy Award with members of the

ART & KRIMES BY KRIMES team, including producers Amanda Spain and Ben Murray,

film participants Jesse Krimes, Jared Owens, and Russell Craig, and animator Molly Schwartz.

You talked about what you look for in a filmmaker, as a director, what do you look for in a producer?

Well, at that moment, I wasn’t actively searching for a producer, but Kristin, in her astute way, probably knew that it would benefit me and Amanda to meet. Amanda and I complimented each other really well. She had experience working in big teams on commissioned series in addition to indie work. It was cool to hear how she would approach things and her energy and efficiency were amazing. I am always looking for someone who compliments me with different skill sets, yet can see eye-to-eye with me to focus on the project’s North Star. What I want in a producer is someone who sees the vision and believes in it deeply, and who will be willing to tap into their networks and remain devoted to the team through inevitable challenges.

Do you have trouble turning off your producer brain when you direct?

Oh, yes, it’s hard. I have to see it as a superpower though. When I’m producing with directors, I know what it’s like to have to make all the decisions right now for everyone. I know what it feels like to have your work really tethered to your identity in a way that I don’t particularly feel when I’m producing. That helps me when I am producing to have really meaningful conversations with directors and get what I need as a producer and give them what they need as a director. And when I’m directing, it helps me to be able to speak the same language as my producer and understand where they’re coming from. My experience producing makes for good communication with my producers, so they can help protect my vision and guard my creative headspace, and I can let go of what I don’t need to think about. And I deeply value my producers as creative collaborators as well as for their strategic and logistical skills. So the line between “producing” and “directing” is perhaps blurrier for me than it typically is in the industry, and I wouldn’t change that even if I could.

With documentaries, so many films get started with just the director because they have to have something to show to raise money. So, inevitably, they are a producer in some way even just to get to the place of having a dedicated producer.

Yes, it’s fluid and it can be messy. I loved working with Melissa and Trevor, and they owned the project. Josh and I were invested in it and very involved in key decisions as producers. We were deep collaborators, but the directors held the controls at the end of the day, which in that case was as it should be. It’s an interesting space to work in because assumptions can be all over the place with what a producer is. Financiers, vendors, crew, and studios can have certain expectations about the power we hold on documentary projects, which aren’t always accurate. I try to be clear with directors, crew, and financiers who work with me about my role and capacity as a producer on a project. A lot of it is just finding people you can work with effectively and being an open communicator.

Do you feel there is a responsibility as the producer to get your subject’s message out in the world, say through an impact campaign? Or is making the movie enough of a contribution?

I’ve never felt like I’ve had to do that work, but I’m drawn to it in many cases. With WILDCAT, we had Amazon Studios on board pretty early and they did some outreach in the veterans community and we did special screenings with Veterans in Media and Entertainment that Harry attended, and those included a fair amount of disabled audience members, which was amazing. Another facet of impact on that film was our team’s work with Amazon Studios to create accessibility assets like captioning and audio description earlier in the post-production process than they might have done on other projects, and to do them as part of our creative team’s deliverables rather than tacked-on by vendors at the end. Our post-production executive there said that he would carry this forward as a best practice, and when I looked at the Sundance Film Festival lineup the following year, Amazon was one of the only studios to have not only delivered all of its festival films with captioning as required, but they offered open caption screenings and audio description. I don’t credit this entirely to WILDCAT, but do feel proud of having contributed to positive change in the industry through our team’s advocacy and example.

With ART & KRIMES BY KRIMES, it was different. It was an indie, and Amanda, Ben, and I didn’t know if it would sell. It took time for the film to catch the eye of Sheila Nevins and her team at MTV Docs. We’d planned to get the film out there regardless of sales, because the people in the film trusted me with their story, and we owe it to them to share the film as widely as possible. So, Amanda and I devised plan A, B, and C. Your plan A is not to sell the film at a Sundance premiere. Your Plan A has to be “I’m going to self-distribute this thing.” Then plan B is, “Maybe it sells to a mid-tier distributor,” and plan C is your fortunate, best-case scenario. If Plan C happens, you also try to weave in the impact elements of your Plan A. With ART & KRIMES BY KRIMES, we did have a well designed plan for impact, and it dovetailed nicely with the work that our main subject Jesse Krimes was already doing. I didn’t know when I started the film that he would found a non-profit, called The Center for Art and Advocacy, which became a partner for our impact campaign. We raised funding from donors to screen the film at venues ranging from San Quentin Prison to the Kennedy Center in DC to MOCA in LA. We targeted the art world and screenings inside the carceral system.

The impact of that project worked out especially well because MTV Docs and Paramount+ bought the film. They were a partner where, on paper, they didn’t allow us to do any community screenings, but in practice they were supportive of us doing that for a period of time. They understood it was helping get the word out about viewership, awards, and publicity. It was a valuable thing that we had that plan. I encourage everyone to plan for impact or self-distribution. If you get stuck in a place where your film’s already done and you don’t have that Plan A to self-distribute, you’re in trouble. And if it does happen that a distributor acquires the film, you pivot to Plan C and you’re in a better position to support distribution with a robust impact campaign.

In terms of your own sustainability, how are you making it work? Is producing and directing your full-time job?

Right now, I am filmmaking full-time. I’m amazed and grateful to say that. I studied architecture before I took the leap into filmmaking and I was an academic tutor for the first 15 years of my career. That’s how I paid the bills, because there was very little money from the grants I raised for my films to pay myself. In New York City, I taught writing to middle school and high school students and did some college essay support. I worked with child psychologists to provide services to kids who were going through big transitions, whether it was a divorce or a loss or mental health struggles. I loved doing that as it allowed me to work in the evenings while I spent daytime hours working on my films. I could also be on an academic calendar where I could take time off during school breaks to go on shoots. That’s how I made my first films. Not everyone has the privilege or opportunity to have that second gig to make ends meet, whether it’s bartending or whatever else you can do. I didn’t have kids yet, at least not until the last two years of me doing that work before moving into full-time filmmaking. Once I moved to LA, I also taught for a little while at LA Film School. I still supplement my artist/producer income by consulting and mentoring. I am a longtime advisor at Global Media Makers for Film Independent. I’ve been a mentor at Sundance Catalyst, and I often serve on grant juries. As you know, these things don’t pay much, but they help in tight times.

In addition to my pro bono work as a co-founder of FWD-Doc, I do short-term consulting. My fees are often hourly or flat for a certain amount of time. That works out well because I can be involved with different projects when I have time. I look for projects on which I can make a positive difference and the teams are receptive.

Also, I should acknowledge that last year was a surreal situation for me where two films sold in one year. They caught up to each other. I never count on backend payments, but if a film is successful, everyone should be sharing in that wonderful situation. I have a little bit of fuel in the tank this year for development of new projects thanks to those sales of long-term labors of love.

As producers, we can spread things out and find a mix of ways to pay the bills, but it’s not easy. How long will it last? I’m grateful for every day that I can say, “I’m just making films today.”

How do you define success? You just won two Emmys, now what? What is enough?

I won’t lie, holding two Emmys feels sensational. And it’s even better when you’re alongside two teams as talented as mine on ART & KRIMES BY KRIMES and WILDCAT. It’s also legible to people outside the industry. My parents can tell friends that their daughter had films on Paramount+ and Amazon and won two Emmys. It’s cool, and I’m grateful, but it’s not what motivates me.

What matters most to me is a couple of things: One is the relationships of the people I’ve made films with. That sounds cheesy, but these things can be. I’m beyond thrilled for Jesse Krimes, for Harry and Samantha, for Melissa, Trevor and Josh. To have worked with Ben repeatedly and to have him and Amanda win an Emmy was so meaningful to me because I’ve been beyond grateful to have them in my life as my producers. They didn’t take a lot of pay on that project, along with me, for so long, so this recognition means a lot.

The other thing that matters to me is the long game – like that aphorism, “ars longa, vita brevis.” For example, I am heartened that my first film, UNFINISHED SPACES, continues to be watched and make an impact around the world. It was on Netflix, it was on PBS, it went to festivals, it won awards, but the thing that I’m most proud of is that it ended up being acquired by the Museum of Modern Art for their film collection. Making something that outlasts me, which people can connect with long after I’m gone, feels good, so I keep that in mind when the days feel difficult sometimes.

When WILDCAT and ART & KRIMES BY KRIMES were on the awards circuit last year, it was bonkers. I kept posting all this self-promotion, which is not usual for me, and became a little disgusted. Then I told myself not to focus on that. Focus on how many hearts and minds can be touched by these films. That’s what actually matters. One time I was the only person in a yoga class and I pointed this out to the yoga teacher and he said, “Only one person? What are you talking about? That is one whole human being.” It shifted my perspective. I’m here to do this work for that one person who’s watching.

Is there anything I didn’t ask that you want to mention?

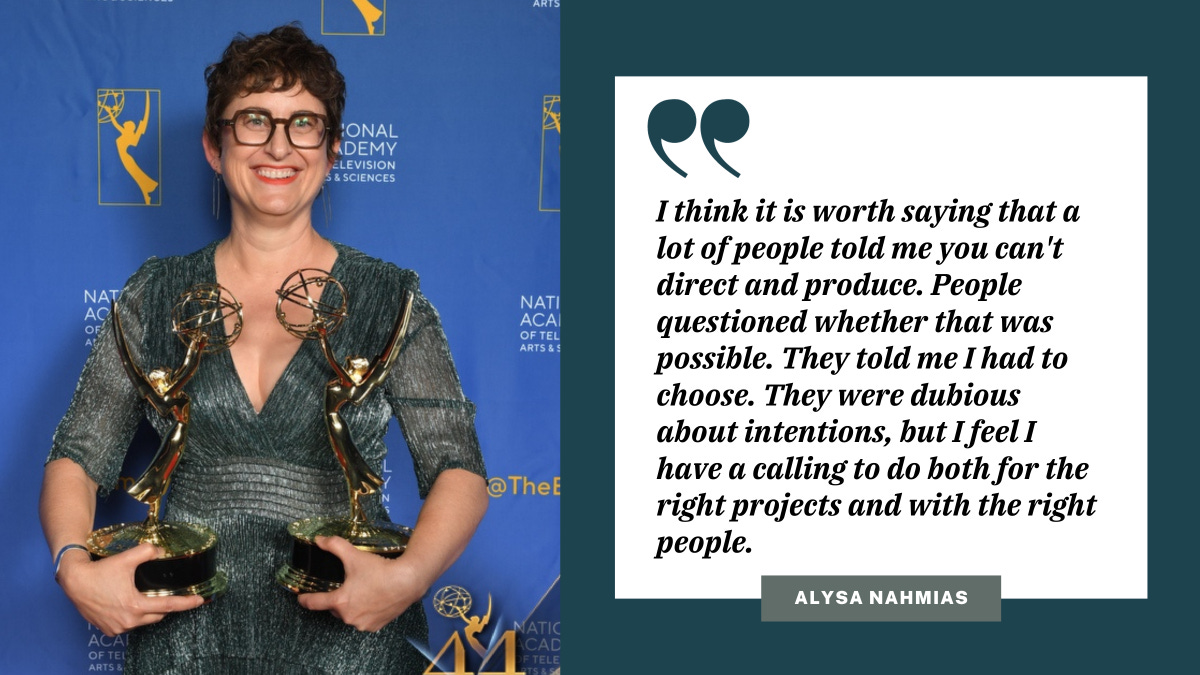

I think it is worth saying that a lot of people told me you can’t direct and produce. People questioned whether that was possible. They told me I had to choose. They were dubious about intentions, but I feel I have a calling to do both for the right projects and with the right people. It’s maybe rarer that you do have a brain and a heart for both producing and directing. I’m inspired by colleagues who also do this, and I’m cheering all of them on – to name a few: Sara Dosa, Day Al-Mohamed, Marilyn Ness, Mridu Chandra, Keith Wilson, and Sara Archambault. It’s something that I think is possible for people who really want to do it, but it can be a little confusing to others. You have to smile through that and show them with your work that it’s possible.